By Steve Haynes

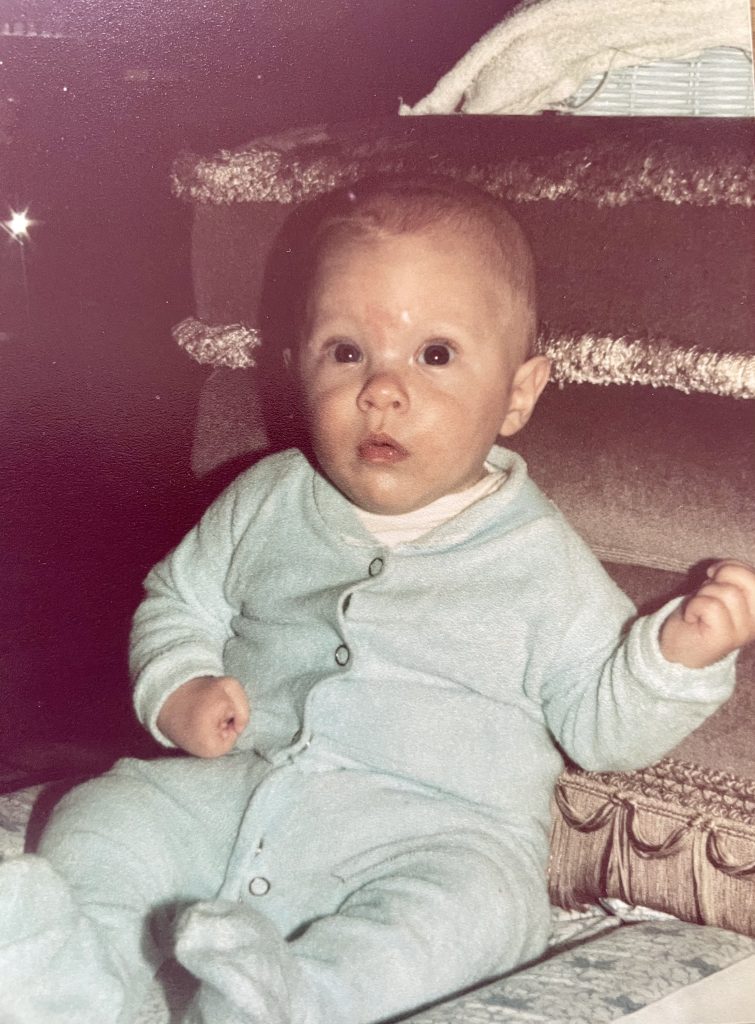

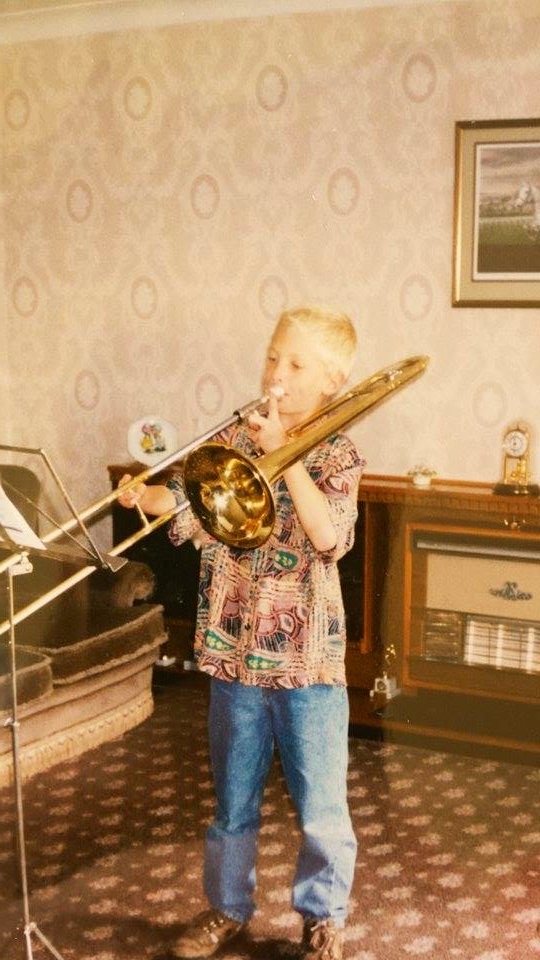

When I was five, I had a bone and a ligament taken from my wrist and grafted into the only two digits on my right hand. I use the term digits, as fingers would’ve been doing some heavy lifting in that sentence. The objective of the operation was to strengthen one and straighten the other, to give my right hand more capacity, it being my dominant side. The operation was unsuccessful, so they tried again when I was eight, this time taking the bone and ligament from a toe on my right foot. This meant being a wheelchair user for a while as I was unable to use crutches. With no wheelchair access at school, I had to be home schooled through this period. I also couldn’t play the trombone for a time, something I loved and ultimately undertook as career. The second operation was successful, until I broke both fingers playing football a few years later.

There aren’t many obstacles my hand has caused me that I haven’t been able to think around. As a trustee for Reach now, I often talk about our superpowers from growing up this way; creativity, self-awareness and determination (my partner would say stubbornness). I used to write in mirror image, which could be related to having to write with my non-dominant hand. Shaking hands has always been a conundrum for me, which I unpacked in a video for our recent How Do You Do It campaign. Other than that, I don’t have any access requirements for my upper limb difference. Sure, I get frustrated when I instinctively use my right hand first, but I also weight train (using straps so my wrists take the weight) and play golf.

As a trustee for Reach now, I often talk about our superpowers from growing up this way; creativity, self-awareness and determination (my partner would say stubbornness).

I’m interested then in why my parents chose to subject me to these two operations, especially now I’m a passionate advocate of the social model of disability. My parents always brought me up to get on with life and not be phased. I’m not sure I would have worked in the West End for ten years without this mindset. I’m also not sure whether this mindset led to me having a breakdown in my thirties, when it finally dawned on me I was different.

I have such a positive relationship with my parents now; I love them and respect them enormously, so I wanted to understand their thought processes from day one.

“There was no information back then [in the 80s] and we didn’t find Reach until you were a child,” my dad told me. “We were lucky to have a supportive GP whose partner was a paediatrician.”

“The first surgeon we saw wanted to cut away the middle section to give a more distinctive pincer movement,” my mum continued, “but we were adamant nothing should be removed from the little you had.” In hindsight this was an excellent decision, as now my strongest grip comes between what would be my thumb and first finger knuckle.

Toe transfers were new and my parents spent many hours travelling from Yorkshire to London to discuss this option. They ultimately settled though on a surgeon closer to home, who my dad tells me really listened to what I wanted. What I find interesting here is even at five, I didn’t have the unrealistic expectation of my right hand being like my left. I’m told instead I asked for one finger to be straighter and the other to be stronger, which shows a level of acceptance I hadn’t realised I had. Whilst the notion of me calling the shots is comforting, I’ll never know whether at that age I fully appreciated the impact and consequences of what I was signing up for. It was new territory for the surgeon, who admittedly got it right second time. My feeling is this would’ve never been permanent though, given the delicate structures of my hand, and me being an active child. I take solace though that the surgeon took learnings from my operations.

On reflection, surgery wasn’t right for me. I went through two significant operations and the outcome was the same as what I already had. It took me away from activities I loved and must’ve, albeit subconsciously, emphasised my feelings of difference and needing to be fixed. My right hand was never going to be like my left, and my efforts may have been better spent continuing to work towards self-acceptance and being kind to myself. It’s hard to be honest with ourselves but openness with those we trust helps. I know my parents did their best for me at that time and I’ll always love them for that. I’m also glad society’s attitudes are changing, and I’m proud of the work Reach does to support this.

Shared from Within Reach Magazine Summer 2024. Flick through the whole magazine here!